Natron Energy, a Santa Clara, California-based sodium-ion battery startup, ceased operation on 3 September due to funding issues. Just a year ago, the company made headlines for its plans to build a first-of-its-kind US $1.4 billion factory in North Carolina to manufacture up to 14 gigawatt-hours of sodium-ion batteries. While experts say Natron’s closure shouldn’t be taken as a harbinger for the rest of the emerging industry in the United States, they acknowledge that the West is behind China, which is leveraging its dominance in lithium-ion batteries to forge ahead on sodium-ion battery manufacturing.

In the U.S., sodium-ion startups like Natron, which launched in 2012, tend to rely on goodwill from funders, says K.M. Abraham, a retired research professor at Northeastern University in Boston and CTO of lithium-ion battery consulting firm E-KEM Sciences. This can pose challenges for companies when funding timelines outpace innovations.

“Companies aren’t able to make progress quickly enough to keep up with pressure exerted by the investors,” he says.

Natron’s Pioneering Prussian Blue Batteries

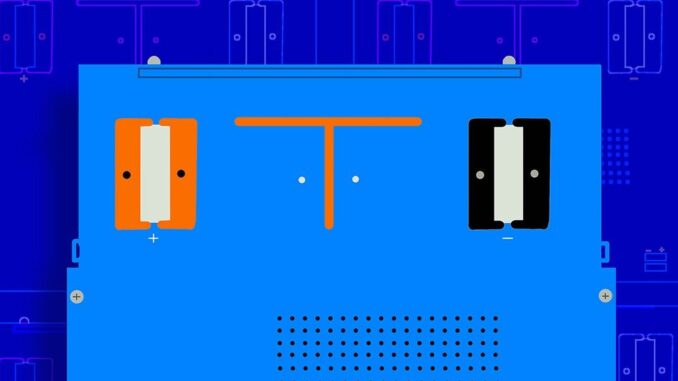

Until recently, Natron was seen as a leader of the pack in the U.S. sodium-ion market. Part of the company’s appeal was its pioneering approach to low-cost electrodes, the conductors at the battery’s positive and negative terminals, which make contact with the non-metallic part of the circuit. The company used Prussian Blue, a pigment found in paints and dyes, to make both the cathode and anode for its three battery systems. In addition to having a low material cost, Prussian Blue’s chemical structure has large pores, helping it facilitate faster ion transfer between the electrodes.

Natron was the first in the world to commercialize a sodium-ion battery using Prussian Blue, a real feat considering China’s battery manufacturing might, says Tyler Evans, co-founder and CEO of Mana Battery, a Broomfield, Colorado-based sodium-ion battery cell startup that launched in 2023.

“They were doing it in the West, and they were scaling a technology that was relatively low energy density for a very specific market segment,” says Evans about Natron’s products.

Mana is another U.S. startup focusing on bringing sodium-ion batteries to market.Nicholas Singstock/Mana

That market included grid storage, data center power backups, and electric vehicle charging stations—large-scale stationary applications where attributes like safety and cost rank higher than energy density. Natron’s success in this space, including its plans for the North Carolina factory, prompted questions about whether sodium-ion could emerge as a direct replacement for lithium-ion batteries. United Airlines and Chevron were on the list of Natron’s investors.

But Evans says scaling up a low-energy density product while building out manufacturing lines is expensive. “If you think about building a manufacturing facility where you want to produce 10 gigawatt hours of batteries, if your energy density is very low, producing an equivalent number of batteries requires more manufacturing lines,” Evans says.

“If you think about building a manufacturing facility where you want to produce a gigawatt-hour of battery manufacturing capacity, if your energy density per battery cell is very low, producing that capacity requires more manufacturing lines,” Evans says, meaning significantly more capital and operational expenditure in an already capital-intensive undertaking.

In 2023, Natron’s systems made it to market. The company partnered with Encorp to deploy the industry’s first multi-megawatt class power platform for industrial applications. A year later, in 2024, Natron opened the U.S.’s first commercial scale manufacturing facility in Holland, Michigan to supply data centers with energy storage. The U.S. Department of Energy’s ARPA-E program provided $19.8 million to Natron as part of a $300 million facility upgrade to transition from lithium-ion battery manufacturing to sodium-ion battery manufacturing. That facility shut its doors at the same time as Natron’s California headquarters on 3 September.

A request for comment from Natron resulted in an automated message to contact the company’s primary shareholder, Sherwood Partners. Sherwood Partners did not respond to a request for comment.

Sodium-Ion vs. Lithium-Ion Battery Costs

Adrian Yao is the founder and team lead of Stanford’s STEER initiative, a DOE-funded research program. He’s also an author of a January 2025 paper assessing how sodium-ion batteries measure up to lithium-ion batteries in terms of technology and cost.

While he was impressed with Natron’s technology and product, he says that the company may have been ahead of the curve on the data center market niche it had carved out for itself. “Hyperscalers right now, their primary concern is just getting connected and building data centers,” says Yao. “I think timing on that cycle may be early, and it’s unfortunate things don’t always work out.”

Natron joins Stanford spin-out Bedrock Materials as the second sodium-ion company to fold this year. Bedrock cited market and innovation challenges for its April closure.

“The battery business is very difficult. There are a lot of tombstones,” says Andrew Thomas, president and cofounder of Acculon Energy, a Columbus, Ohio-based startup marketing two battery modules with sodium-ion cells for industrial energy and EVs that travel at low speeds, like golf carts. Unlike Natron, Acculon, which launched in 2022, employs more traditional layered-metal oxides and other sodium chemistries.

Thomas says it’s this distinction that makes it hard to draw conclusions about the U.S. sodium-ion battery industry as a whole in light of Natron’s closure. Comparing different sodium-ion chemistries, like Prussian Blue or layered metal oxides, is like comparing apples to oranges.

“I don’t think one failure is representative of a country being unable, but we’re at a significant disadvantage given the installed base in China,” Thomas says.

China’s Dominance in Battery Manufacturing

China has long dominated the battery industry, and sodium-ion batteries are no exception. Today, China produces more than 75 percent of batteries sold globally, according to the International Energy Agency. On the sodium-ion front, developers like CATL have moved into second-generation batteries, with the April launch of Naxtra, a brand geared toward EV applications.

Yao says he’d like to see the U.S. concentrate its focus more on building up its manufacturing prowess to compete with China. “My broader critique of the Western Hemisphere in terms of our thinking and obsession with trying to innovate ourselves out of the problem, is that we focus too much on tech,” Yao says. “We have very little manufacturing experience… Our yield rates are abysmal, and our workforce is not trained.”

Founders like Evans and Thomas are optimistic about their prospects as growing demand for grid storage, data centers, and low-cost mobility applications drives the need for applications they say sodium-ion batteries are uniquely equipped to support in terms of temperature range, safety, and cost metrics. When it comes to manufacturing, Mana is taking a page from China’s playbook by partnering with existing manufacturers to scale up production.

Evans says there’s an appetite for this kind of partnership in the U.S. right now. “I think it’s a commercialization sweet spot that’s specific to sodium.”

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

Be the first to comment